Photo: FIRST UNITED is redeveloping their site at Gore and Hastings Street to include 4 floors of programming and services, and 7 floors of affordable housing which includes 35 units of supportive housing, operated by Lu’ma Native Housing Society. Render by Arcadis Architects.

Insights: What is supportive housing, who is it for, and how does it work?

Supportive housing as a term has been in the media a lot over the last few years, mostly as a result of neighbourhood campaigns against this type of housing and reports that link it to public safety issues.

But is this fair and, more importantly, a complete picture?

In this edition of Insights we take a look at what supportive housing is, who it is built for, and what its impacts are on residents and the wider community.

What is supportive housing?

The term “supportive housing” can mean a lot of things, but at its core it’s a safe and secure home where someone can stabilize their personal situation and establish connections with their community.

For BC Housing buildings, residents often benefit from employment connections, 24/7 access to support staff, and at least one hot meal per day. But there are other models as well, including small group homes for single mothers and their children or homes with extra services to support seniors.

Why do we need it?

In the case of seniors especially, most people can probably understand why supportive housing exists. As we age, we often need more care – especially to deal with complex health challenges. Maybe an older person has mobility issues, combined with less mental capacity, as well as an acute illness that requires medications administered on a regular basis. But seniors are not the only segment of our society that develop complex needs that require extra support.

A record number of our neighbours are struggling to overcome trauma and health challenges while facing outright homelessness or very precarious housing situations. Consider that while Vancouver’s population grew by 8% between 2018 and 2023, the number of people experiencing homelessness grew by 14%. This means that folks who were otherwise housed fell into homelessness, and it’s not hard to understand why. In 2021, there were 62,500 low-income households in Vancouver who paid more than 50% of their income on rent and were very vulnerable to homelessness as a result.

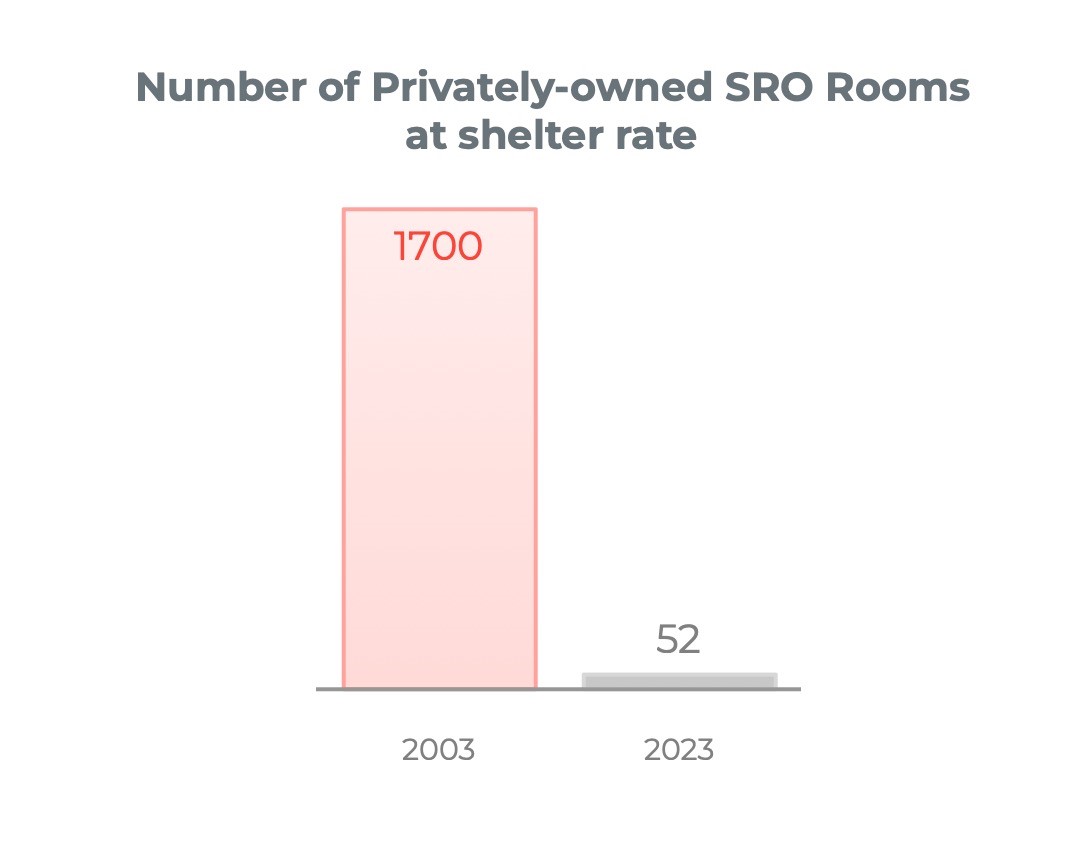

And if you lived in a privately-owned SRO room, things were even more dire. The number of these rooms available at shelter rates ($375/month at the time) decreased from 1,700 in 2003 to just 52 rooms in 2023 (Survey of Low-income Rental Options).

By 2023 when Vancouver completed its last Point in Time Count, at least 2,420 were experiencing homelessness – and 63% of these people said they were living with two or more health concerns.

If you live in Vancouver, especially as a renter, this stress is probably familiar. Many of us are already struggling in Vancouver, living paycheque to paycheque just to pay the rent and cover the basics. Now imagine you have a health condition and for whatever reason you lose your job. How easy would it be to end up without a home?

This is why more often than not, people who end up needing housing support are our neighbours and not from some place far away. 78% of individuals interviewed in Vancouver’s Point in Time count said that they were living here when they became homeless, and 62% said they had lived here for over 5 years.

How does supportive housing help?

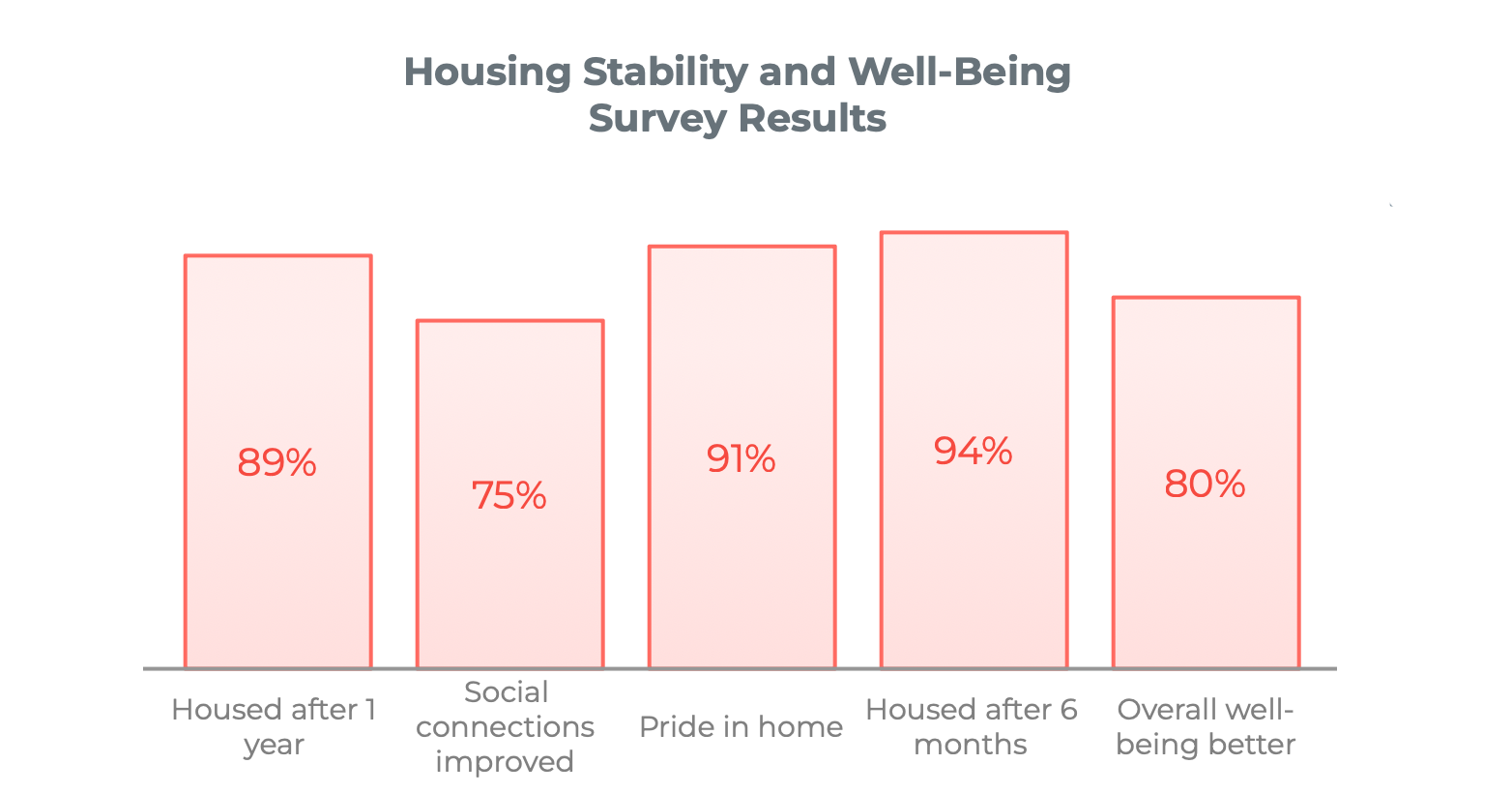

In response to this shortage, the provincial government, working with the city and the non-profit sector, has taken measures to protect the SRO stock and to build affordable rental housing. Some people, particularly those who have experienced homelessness for an extended period and who also face health issues, not only need safe and affordable homes, but need additional support such as healthy food, health care, and help in crisis management so they can rebuild their lives and exit homelessness permanently. The effectiveness of supportive housing is well documented locally:

|

Study |

Findings |

|

Case study of Sanford Apartments MPA Housing / BC Housing |

|

|

Resident Outcomes Evaluation, Temporary Modular Housing BC Housing |

|

|

Mental Health Commission of Canada |

|

Well-planned and resourced supportive housing can blend into the fabric of our neighbourhoods and not only have no negative impacts but create positive impacts for both their residents and their neighbourhoods. Research shows that supportive housing actually reduces pressure on public service costs. Residents have 32% lower health and correctional institution costs than people who are experiencing homelessness and are 64% less likely than shelter clients to require ambulance services.

Do we have enough supportive housing already?

Supportive housing makes up very little of the current housing stock in Vancouver or Metro Vancouver. Most homes across the Metro Vancouver region are private, as well as some non-market housing such as non-profit and co-op housing. There is only a small amount of supportive housing – 3% in Vancouver and 2% in the region as a whole (calculated from Metro Vancouver Housing Data Book 2023).

Most new apartments that offer permanent supportive housing have been built outside of Vancouver in Surrey, Burnaby, New Westminster, and Maple Ridge. Vancouver has added housing mainly through building conversion and temporary modular housing as a quick response to encampments, the pandemic, and the loss of SROs.

These measures have been necessary to address the mounting health and homelessness crises. But significantly more needs to be done. Not only do most of these units in Vancouver need to be replaced by permanent, well-designed supportive housing that is self-contained, but considerably more needs to be built.

Demand for permanent supportive housing units in Vancouver

|

Improvement to existing At least 4,000 homes |

This would accommodate:

|

|

Net new At least 5,800 homes

|

This would accommodate people who are currently or at risk of being unhoused who could benefit from housing supports. At least:

|

Note: This estimate does not include other types of supportive housing, for instance assisted living seniors, community living and transitional housing. It also does not consider replacement of aging supportive housing outside of non-market SROs.

Each municipality in Metro Vancouver has a responsibility to serve its community, while also balancing the need for new supportive housing across the region. Most people in Vancouver who are experiencing or are at imminent risk of homelessness are citizens of the city and should be able to live where they have social connections and community support. At the same time, other municipalities in Metro Vancouver must develop significantly more supportive housing to respond to growing homelessness locally (often at a rate 6x that of Vancouver for many municipalities).

Supportive housing is critical to tackling homelessness and making everyone safer

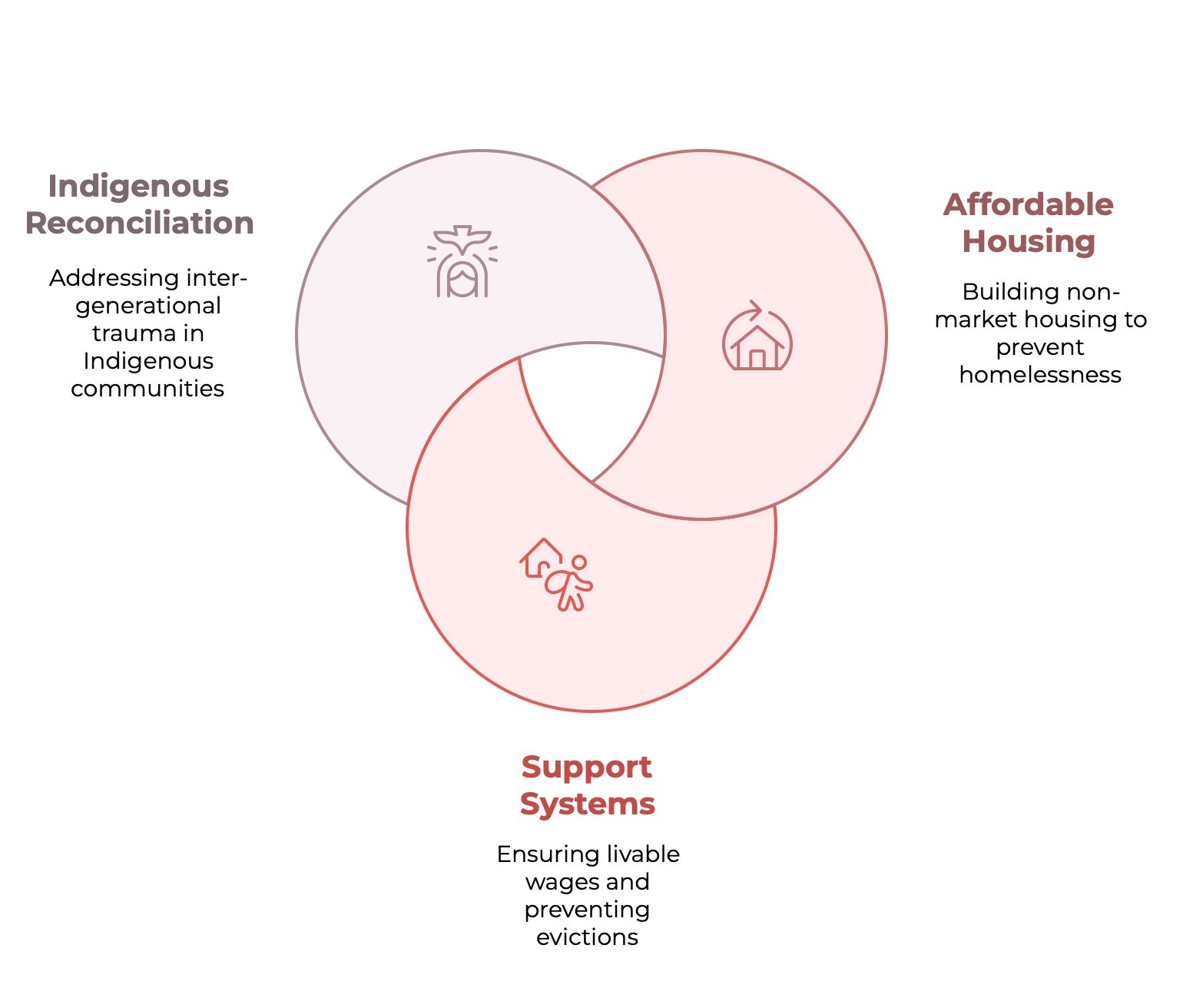

We cannot address homelessness, poverty, and human distress by stopping the construction of new supportive housing in Vancouver and by weakening social supports in the Downtown Eastside. Instead, we need to work together as a region to build a stronger support system. Successfully addressing homelessness is a complex undertaking, but one that is possible if we work together to:

-

Stem new flows into homelessness by building permanently affordable non-market housing, ensuring that wages and income are livable, and preventing evictions.

-

Support everyone without a home to be successfully housed.

-

Meaningfully act on Reconciliation with Indigenous peoples to address inter-generational trauma that has contributed to the disproportionate share of Indigenous people among those who are experiencing homelessness.

Providing this housing can be accomplished through both dedicated supportive housing built for this purpose as well as non-market housing that provides secure, suitable units that can rented at shelter rates and which could be used for Housing First approaches that support housing stability and recovery. The benefits of providing more supportive housing are impactful for everyone and will significantly reduce, if not end, chronic homelessness and create safer communities. Most importantly, it will help enable people to live safe and dignified lives.

Key takeaways

- People who need supportive housing are our neighbours. 78% of those asked saying they lived in Vancouver when they became homeless, and 62% said they had lived here for over 5 years.

- Supportive housing helps people stay housed and stabilize their lives. Studies show that up to 94% of residents remained housed after six months and 89% were still housed after a year

- Supportive housing saves public money. Research shows that people in supportive housing have 32% lower health and correctional institution costs and are 64% less likely to require ambulance services compared to those experiencing homelessness.

Sources

(1) People currently living in non-market SROs: Table 1, Units owned by BCH Housing, City of Vancouver, Non-Profit, Chinese Benevolent Society SRO Update, 2023 Low-Income Housing Survey and Proposed SRA By-law Amendments

(2) People living in temporary modular housing: Tabulated from projects listed on City of Vancouver Website (accounting for closure of Larwill place)

(3) People currently experiencing homelessness: Vancouver 2023 Point-in-time Count multiplied by the share likely in need of supportive housing (p15, City of Vancouver, Uplifting the Downtown Eastside and Building Inclusive Communities that Work for All Residents Motion) This is likely an underestimate since the point in time count is known to underestimate homelessness.

(4) People marginally housed in private SROs: # private SRO Rooms in 2023 multiplied by 60%, the share of residents in private SROs that pay more than 50% of their income on rent (City of Vancouver, SRO Update, 2023 Low-Income Housing Survey and Proposed SRA By-law Amendments)

(5) People at high-risk of homelessness (non-SRO): Number of people (15+) living in low-income households that pay more than 50% of their income on rent in Metro Vancouver (Statistics Canada ) multiplied by Vancouver’s share of the regional population (2012 Census of Population), multiplied by the share of the Canadian population that have unmet needs relating to mental health (Statistics Canada, Mental Disorders in Canada 2022).